If I know a song of Africa, of the giraffe and the African new moon lying on her back, of the ploughs in the fields and the sweaty faces of the coffee pickers, does Africa know a song of me? Will the air over the plain quiver with a colour that I have had on, or the children invent a game in which my name is, or the full moon throw a shadow over the gravel of the drive that was like me, or will the eagles of the Ngong Hills look out for me?

I had a farm in Africa at the foot of the Ngong Hills. The Equator runs across these highlands, a hundred miles to the north, and the farm lay at an altitude of over six thousand feet. In the day-time you felt that you had got high up; near to the sun, but the early mornings and evenings were limpid and restful, and the nights were cold.

The geographical position and the height Of the land combined to create a landscape that had not its like in all the world. There was no fat on it and no luxuriance anywhere; it was Africa distilled up through six thousand feet. like the strong and refined essence of a continent. The colours were dry and burnt. like the colours in pottery. The trees had a light delicate foliage, the structure of which was different from that of the trees in Europe; it did not grow in bows or cupolas, but in horizontal layers, and the formation gave to the tall solitary trees a likeness to the palms, or a heroic and romantic air like full-rigged ships with their sails furled, and to the edge of a wood a strange appearance as if the whole wood were faintly vibrating. Upon the grass of the great plains the crooked bare old thorn trees were scattered, and the grass was spiced like thyme and bog-myrtles; in some places the scent was so strong that it smarted in the nostrils. All the flowers that you found or plains, or upon the creepers and liana in the native forest, were diminutive like flowers of the downs – only just in the beginning of the long rains a number of big, massive heavy-scented lilies sprang out on the plains. The views were immensely wide. Everything that you saw made for greatness and freedom, and unequaled nobility.

The chief feature of the landscape, and of your life in it, was the air. Looking back on a sojourn in the African highlands, you are struck by your feeling of having lived for a time up in the air. The sky was rarely more than pale blue or violet, with a profusion of mighty, weightless, ever-changing clouds towering up and sailing on it, but it has a blue vigour in it, and at a short distance it painted the ranges of hills and the woods a fresh deep blue. In the middle of the day the air was alive over the land, like a flame burning; it scintillated, waved and shone like running water, mirrored and doubled all objects, and created great Fata Morgana. Up in this high air you breathed easily, drawing in a vital assurance and lightness of heart. In the highlands you woke up in the morning and thought: Here I am, where I ought to be.

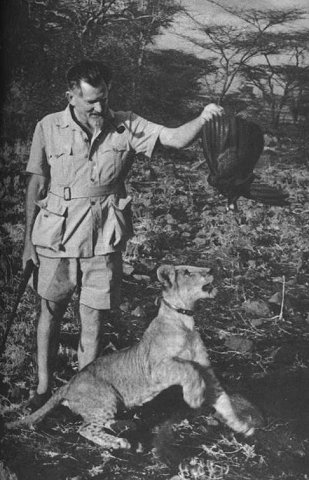

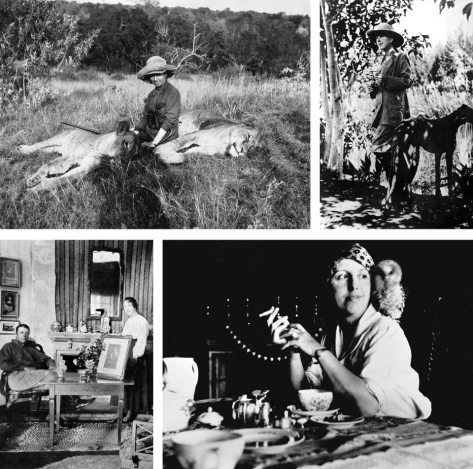

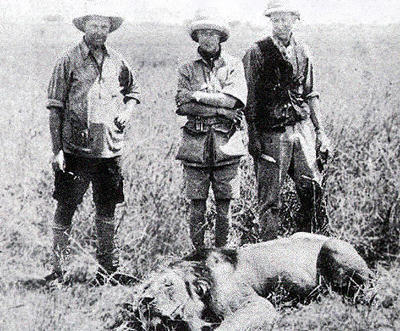

There is something about safari life that makes you forget all your sorrows and feel as if you had drunk half a bottle of champagne — bubbling over with heartfelt gratitude for being alive. One only feels really free when one can go in whatever direction one pleases over the plains, to get to the river at sundown and pitch one’s camp, with the knowledge that one can fall asleep beneath other trees, with another view before one, the next night. I had not sat by a camp fire for three years, and so sitting there again listening to the lions far out in the darkness was like returning to the really true world again, where I probably once lived 10,000 years ago…

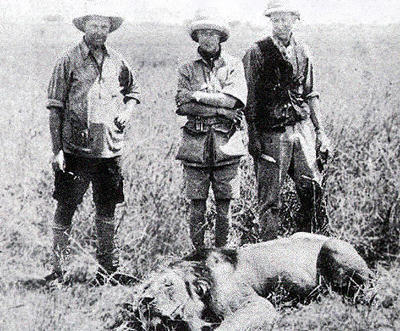

Out on the Safaris, I had seen a herd of buffalo, one hundred and twenty nine of them, come out of the morning mist under a copper sky, one by one, as if the dark and massive, iron like animals with the mighty horizontally swung horns were not approaching, but were being created before my eyes and sent out as they were finished. I had seen a herd of elephant travelling through dense native forest, where the sunlight is strewn down between the thick creepers in small spots and patches, pacing along as if they had an appointment at the end of the world.

It was, in giant size, the border of a very old, infinitely precious Persian carpet, in the dyes of green, yellow and black brown. I had time after time watched the progression across the plain of the giraffe, in their queer, inimitable, vegetative gracefulness, as if it were not a herd of animals but a family of rare, long stemmed, speckled gigantic flowers slowly advancing. I had followed two rhinos on their morning promenade, when they were sniffing and snorting in the air of the dawn, which is so cold that it hurts in the nose, and looked like two very big angular stones rollicking in the long valley and enjoying life together. I had seen the royal lion, before sunrise, below a waning moon, crossing the grey plain on his way home from the kill, drawing a dark wake in the silvery grass, his face still red up to the ears, or during the midday siesta, when he reposed contentedly in the midst of his family on the short grass and in the delicate, spring like shade of the broad acacia trees of his park of Africa.

The natives have, far less than the white people, the sense of risks in life. Sometimes on a Safari, or on the farm, in a moment of extreme tension, I have met the eyes of my native companions, and have felt that we were at a great distance from one another, and that they were wondering at my apprehension of our risk. It made me reflect that perhaps they were, in life itself, within their own element, such as we can never be, like fishes in deep water which for the life of them cannot understand our fear of drowning. This assurance, this art of swimming, they had, I thought, because they had preserved a knowledge that was lost to us by our first parents; Africa, amongst the continents, will teach it to you: that God and the Devil are one, the majesty co-eternal, not two uncreated but one uncreated, and the natives neither confounded the persons nor divided the substance.

The natives were Africa in flesh and blood. The tall extinct volcano of Longonot that rises above the Rift Valley, the broad mimosa trees along the rivers, the elephant and the giraffe, were not more truly Africa than the natives were, small figures in an immense scenery. All were different expressions of one idea, variations upon the same theme. It was not a congenial up-heaping of heterogeneous atoms, but a heterogeneous up-heaping of congenial atoms, as in the case of the oak leaf and the acorn and the object made from oak. We ourselves, in boots, and in our constant great hurry, often jar with the landscape. The natives are in accordance with it, and when the tall, slim, dark, and dark eyed people travel, always one by one, so that even the great native veins of traffic are narrow footpaths, or work the soil, or herd their cattle, or hold their big dances, or tell you a tale, it is Africa wandering, dancing and entertaining you. In the highlands you remember the Poet’s words: Noble found I ever the native, and insipid the immigrant.

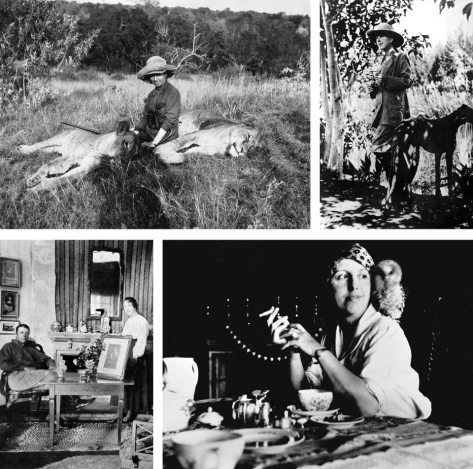

There was a place in the hills, on the first ridge in the game reserve, that I myself at the time when I thought that I was to live and die in Africa, had pointed out to Denys as my future burial-place. In the evening, while we sat and looked at the hills, from my house, he remarked that then he would like to be buried there himself as well. Since then, sometimes when we drove out in the hills, Denys had said: “Let us drive as far as our graves.” Once when we were camped in the hills to look for buffalo, we had in the afternoon walked over to the slope to have a closer look at it. There was an infinitely great view from there; in the light of the sunset we saw both Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro.

Perhaps he knew, as I did not, that the Earth was made round so that we would not see too far down the road.

Here in the early afternoon they brought out Denys from Nairobi, following his old Safari-track to Tanganyika, and driving slowly on the wet road. When they came to the last steep slope, they lifted out, and carried the narrow coffin, that was covered with the flag. As it was placed in the grave, the country changed and became the setting for it, as still as itself, the hills stood up gravely, they knew and understood what we were doing in them; after a little while they themselves took charge of the ceremony, it was an action between them and him, and the people present became a party of very small lookers-on in the landscape.

Denys had watched and followed all the ways of the African Highlands, and better than any other white man, he had known their soil and seasons, the vegetation and the wild animals, the winds and smells. He had observed the changes of weather in them, their people, clouds, the stars at night. Here in the hills, I had seen him only a short time ago, standing bare-headed in the afternoon sun, gazing out over the land, and lifting his field-glasses to find out everything about it. He had taken in the country, and in his eyes and his mind it had been changed, marked by his own individuality, and made part of him. Now Africa received him, and would change him, and make him one with herself.

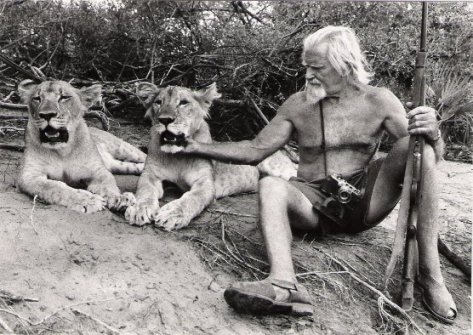

After I had left Africa, Gustav Mohr wrote to me of a strange thing that had happened by Denys’ grave, the like of which I have never heard. “The Masai,” he wrote, “have reported to the District Commissioner at Ngong, that many times, at sunrise and sunset, they have seen lions on Finch-Hatton’s grave in the Hills. A lion and a lioness have come there, and stood, or lain, on the grave for a long time. Some of the Indians who have passed the place in their lorries on the way to Kajiado have also seen them. After you went away, the ground round the grave was levelled out, into a sort of big terrace, I suppose that the level place makes a good site for the lions, from there they can have a view over the plain, and the cattle and game on it.”

It was fit and decorous that the lions should come to Denys’s grave and make him an African monument. Lord Nelson himself, I have reflected, in Trafalgar Square, has his lions made only out of stone.

Exerpts

(by Karen Blixen)